Ransomware in Australia: Legal Liability, Notifications and Your Obligations

Ransomware in Australia is on the rise! As a result, regulators are paying more and more attention to these attacks and the way impacted organisations respond. The increasing legal risk and notification obligations and rapidly changing regulatory environment are challenging to keep pace with. This is why we’ve put together this guide to some of the notification obligations and legal liabilities that might arise from a ransomware attack in Australia.

What is Ransomware?

Ransomware is a type of malware that prevents you from accessing your computer (or the data that is stored on it). The computer itself may become locked, or the data on it might be stolen, deleted or encrypted.

Some ransomware will also try to spread to other machines on the network, which is what happened with the Wannacry malware that dramatically impacted the UK hospital system in May 2017.

Most ransomware attacks are targeted at important organisational assets, locking them down and preventing access, and crippling operations until the systems or data can be restored.

Usually, a ransomware attack comes with a request to contact (and pay) the attacker via an anonymous email address or follow instructions on an anonymous web page. The payment is invariably demanded in a cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin and will be made in exchange for the attacker unlocking your computer, or other impacted organisational assets or (re)allowing access your data.

Attackers may also threaten to publish data if payment is not made.

Ransomware Attacks on the Rise

The recently published Sonic Wall Cyber Threat Report cited a 105% year-over-year increase in ransomware attacks in 2021.

Other startling figures revealed in the report include:

- There are nearly 20 ransomware attempts every second.

- There were more ransomware attempts in the first half of 2021 than in all of 2020, and more still in the second half.

- Ransomware rose 122% in Asia in 2021.

Additionally, the report revealed the rising trend of double and triple extortion – where the individuals whose data is stolen in ransomware attacks are contacted by the malicious actor to pay personally. This was highlighted in the October 2020 Vastaamo attack where an attacker exfiltrated employee and patient data from a psychotherapy provider. They then requested payment from Vastaamo, the provider, before individually contacting the patients and demanding they pay too in exchange for not leaking their therapy session notes.

What’s Driving the Increasing Ransomware Attacks?

There is no reason criminal organisations can’t borrow franchise and distribution network business models from the non-criminal world (and they do). The Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) model is an example of this. Criminals are now using ‘make-a-ransomware’ off-the-shelf toolkits which are made available to ‘distributors’ by ‘franchisees’ for a one-off payment or a share of the profits.

Avaddon is a high-profile example of this distribution model in the real world. Avaddon first appeared in March 2020, functioning as a ransomware-as-a-service operation, providing a portal for affiliates to generate and use copies of their crypto-locking malware. Every time a victim paid a ransom, the operator and affiliate shared the profits.

Like many operations, Avaddon also ran a dedicated data leak site, where non-paying victims could be named and shamed and extracts of data stolen from their infrastructure leaked to increase the pressure to pay a ransom.

As the result, criminal groups are increasingly securing significant ransom payments from large profitable businesses who cannot afford to lose their data to encryption or to suffer the down time while their services are offline. In essence, the RaaS model and the market for ransomware has become increasingly “professional”.

Ransomware and the Law in Australia

There are many issues raised by a ransomware attack if you are unlucky enough to be a victim. One of those is the potential legal liabilities that might come from the attack.

In Australia, an organisation’s legal, reporting, and notification obligations following a ransomware attack are made up by a patchwork of laws, including:

- The Data Breach Notification Scheme, under the Privacy Act 1988.

- New security and reporting obligations under the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Act 2021 (SLACI Act)

- Obligations to secure your personal information pursuant to APP 11 of the Privacy Act 1988.

- Obligations to take reasonable care under the Corporations Act.

- Other sector or organisation specific reporting requirements.

There are also some new obligations on the horizon.

Ransomware and Data Breach Notification Scheme

The Data Breach Notification Scheme in Australia requires organisations covered by the Privacy Act 1988 to notify affected individuals and the OAIC of an ‘eligible data breach.”

An ‘eligible data breach is one where:

- there is unauthorised access to or unauthorised disclosure of personal information, or a loss of personal information, that an organisation or agency holds

- this is likely to result in serious harm to one or more individuals, and

- the organisation or agency hasn’t been able to prevent the likely risk of serious harm with remedial action.

Is a ransomware attack an ‘eligible data breach’?

The issue for most ransomware incidents will be whether the ransomware attack has involved unauthorised access to, disclosure of or loss of personal information. The short answer is: it depends. It may not be clear whether, as part of executing the ransomware, personal information has been accessed by or disclosed to the attackers. But the OAIC has made it clear that organisations should always undertake an investigation following a ransomware attack, because there will be, at the very least, a suspected data breach.

The OAIC’s guidance outlines that if an organisation:

… cannot confirm whether a malicious actor has accessed, viewed or exfiltrated data stored within the compromised network, there will generally be reasonable grounds to believe that an eligible data breach may have occurred and an assessment under section 26WH will be required.

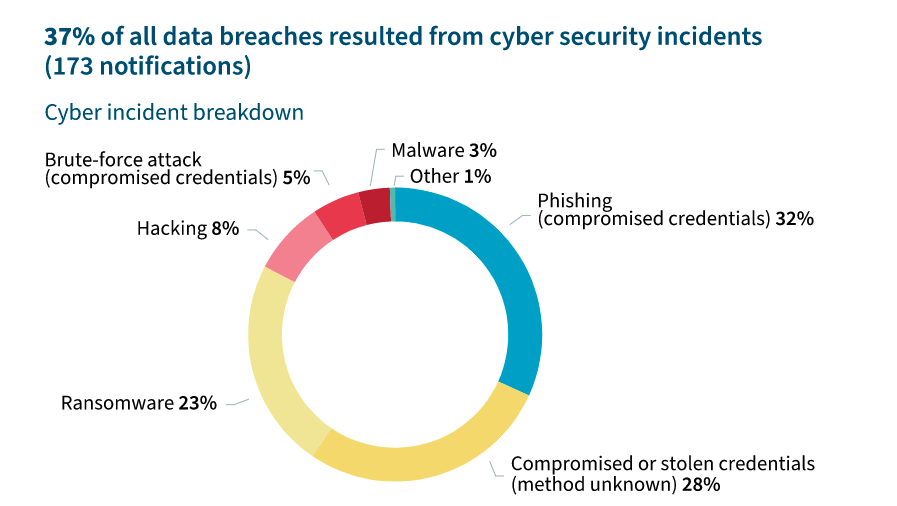

Source: OAIC Notifiable Data Breaches Report July – December 2021

What to do if you suspect there has been an eligible data breach

Section 26 WH gives entities additional time to investigate where they are not entirely sure if a reportable data breach has occurred. The Act provides that, if a data breach is suspected, it must be investigated promptly to determine whether there has been an eligible data breach. It’s essential that the investigation gets underway as soon as possible, since you are required to determine if the suspected data breach is an eligible data breach within 30 days.

How to Complete a Section 26WH Assessment

Given the prevalence of ransomware attacks, the OAIC expects entities to have appropriate internal practices, procedures, and systems in place to undertake a meaningful assessment under section 26WH.

While neither the OAIC nor the Privacy Act outline how an assessment should occur, the OAIC suggests the following three-stage process:

- Initiate: decide whether an assessment is necessary and identify which person or group will be responsible for completing it.

- Investigate: quickly gather relevant information about the suspected breach including, for example, what personal information is affected, who may have had access to the information and the likely impacts.

- Evaluate: make a decision, based on the investigation, about whether the identified breach is an eligible data breach (see Identifying Eligible Data Breaches).

Organisations should document the process for an assessment (ideally before a data breach occurs). The outcome of the assessment should also be documented.

As best practice, entities should:

- have appropriate audit and access logs;

- use a backup system that is routinely tested for data integrity;

- have an appropriate incident response plan; and

- consider engaging a cyber security expert at an early stage to conduct a forensic analysis if a ransomware attack occurs.

Liability for Ransomware Outside of the Notifiable Data Breach Scheme

At the time of writing, there are no cases where an organisation has been successfully sued under Australian common law for a ‘breach of privacy’ or negligence following a ransomware attack. However, there are other legal risks that accompany any ransomware attack, including the following.

Breach of APP 11 under the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)

Organisations covered by the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) must comply with APP 11, which relates to the security of personal information.

Specifically, APP entities must take reasonable steps to protect the personal information it holds from misuse, interference and loss, as well as unauthorised access, modification, or disclosure.

A successful ransomware attack may indicate a failure to take reasonable steps to either prevent the attack or to enable a speedy recovery.

Organisations that notify the OAIC if a data breach relating to a ransomware attack might be subjected to further scrutiny from the Commission, particularly as to what steps the organisation had taken to protect again such attacks.

OAIC investigations can be long, involve significant executive time and lead to the publication of a report which might include unfavourable findings about the organisation’s security practices.

Critical Infrastructure and Ransomware Notifications (SLACI 2021)

The Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Act 2021 (SLACI 2021) introduced new mandatory cyber incident reporting, in addition to other increased security obligations for an expanded critical infrastructure sector. This Act requires reporting to the Australian Cyber Security Center (ACSC) – a different regulator to the OAIC which is responsible for data breaches involving personal data.

Various provisions of the Act, including the cyber incident reporting obligations, only become operable when enabling rules are passed. As at February 2022, there were draft rules relating to the mandatory reporting requirement. These draft rules outline that companies operating within the 9 of the 11 sectors deemed critical infrastructure must report a cyber incident within:

- 12 hours if the incident is having a significant impact on the availability of the asset, and if the report is made verbally, in writing within 84 hours of verbally notifying the ACSC or,

- 72 hours if the incident is having a relevant impact on the availability, integrity, reliability or confidentiality of the asset, and if the report is made verbally, in writing within 48 hours of verbally notifying the ACSC. (See more here)

Failing to comply with this requirement can attract fines up to $55,000.

We covered SLACI 2021 in a previous post, including potential reporting obligations. Read more here.

Breach of the Corporations Act

While there are no director’s duties that specifically refer to the consideration of cyber threats or data privacy and security, directors may be liable following a data breach under the general duty of care and diligence.

Sector or Organisation-Specific Ransomware Notification Requirements

In addition to the above notification obligations, there may be reporting obligations under sector-specific and other legislation. This includes:

- My Health Record Act: Healthcare providers must notify the Australian Digital Health Agency of any potential or actual data breaches relating to the My Health Record system as soon as possible. (Read more here)

- Consumer Data Rights scheme: An opt-in scheme for organisations that comes with additional privacy rights for consumers.

- ASX listing rules: Factors that would reasonably be expected to have a material effect on the price of a listed entity’s securities must be disclosed to the ASX. Data breaches and ransomware attacks may fall under this category and may be required to be disclosed.

- ASIC disclosure obligations for Australian financial services licensees and Australian credit services licensees.

Ransomware payments: to pay or not to pay?

The overwhelming advice from law enforcement and official cybersecurity bodies is not to pay the ransom. Law enforcement in particular do not encourage, endorse, nor condone the payment of ransom demands.

The Australia Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) also strongly recommends that you do not pay. The ACSC advises that, if you do pay the ransom:

- there is no guarantee that you will get access to your data or computer;

- your computer will still be infected;

- you will be paying criminal groups; and

- you’re more likely to be targeted in the future.

The risk of a second attack seems to be supported by evidence.

Boston-based Cybereason found 80% of organizations that previously paid ransom demands confirmed they were exposed to a second attack, according to a commissioned survey of 1,263 cybersecurity professionals in varying industries from the U.S., United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, France, United Arab Emirates and Singapore.

In terms of getting your data back, it seems that ransomware attackers are pretty reliable. Sonos reports that 1% of organizations pay the ransom and never get their files back. Looking at country-specific statistics, Australian organisations are amongst the most willing in the world to pay a ransom if they experience a ransomware attack. Given the average ransom paid by businesses at the end of 2020 was $154,104, this represents a significant risk (and cost) to the average Australian organisation.

Notwithstanding the law enforcement and security professional advice, for many businesses paying the ransom is the only way they will be able to get back to normal operations.

As it stands, it is not currently illegal to pay a ransom following a ransomware attack.

Ransomware Notifications Slated for the Future

We’re anticipating further changes and increased obligations relating to ransomware in the future. Most notably is legislation to implement the government’s Ransomware Action Plan.

In mid-October 2021, Australia’s new Ransomware Action Plan was released by the Department of Home Affairs. It sets out the Government’s immediate strategic approach to tackle the threat posed by ransomware, and builds on the overarching cyber security architecture instigated in the 2016 and 2020 Cyber Security Strategies, and is designed around the framework of the National Strategy to Fight Transnational, Serious and Organised Crime.

“The Ransomware Action Plan takes a decisive stance — the Australian Government does not condone ransom payments being made to cybercriminals. Any ransom payment, small or large, fuels the ransomware business model, putting other Australians at risk,” Minister for Home Affairs Karen Andrews.

It also outlines current initiatives already undertaken by the Government to improve cybersecurity generally, as well as upcoming policy, operational and legislative reforms aimed specifically at disrupting and deterring ransomware attacks.

Ransomware Initiatives by the Australian Government

Mandatory notification requirements: if proposed legislative reforms are enacted, Australian companies with a turnover of $10 million or more will, for the first time, have an express obligation to notify the Australian Government if they are the subject of ransomware incidents.

More powers for law enforcement to investigate and seize ransomware payments.

Tougher new penalties for non-compliance: under the Plan, law enforcement is set to have greater powers to investigate and seize ransomware payments. The Plan proposes new standalone aggravated offences for all forms of cyber extortion and for cybercriminals seeking to target critical infrastructure.

Alignment between related or parallel reporting regimes: the devil will be in the detail, but we expect some alignment with notification requirements under the SOCI Act. We expect further details to emerge following consultation, including what additional information organisations are expected to provide in the event of an attack and in the days that follow.

Payments to ‘designated entity’ attackers may be prohibited: we suspect that, if this comes to pass, there may be a defence available if an organisation undertook due diligence and reasonable precautions to avoid contravening a sanctions law. What this will require in practice is for organisations to conduct sanctions risk assessments and third-party screenings against sanctions lists before making a ransom payment.

We covered the Ransomware Action Plan in more detail in our previous post: https://privacy108.com.au/insights/ransomware-action-plan/

Ransomware Training with Privacy 108

Privacy108 are experts in security awareness training. Our instructors have been delivering security and privacy training for over 15 years.

Your people and their devices are at the front line of ransomware attacks. Ensuring they are properly trained and remain alert and vigilant is a vital part of your ransomware defence program.

Our team can assist with rolling out computer-based training, using existing collateral, or with the development and delivery of more targeted training, including practical lab-based sessions, tailored for your own environment. To help arm your team to deal with ransomware, Privacy108 offer the following:

- Employee security awareness training, focusing on the human-centric attacks;

- Lab exercises to train your front line and incident response teams;

- Ransomware exercises – both tabletop and ‘real’ to truly test your team’s readiness;

- Development of an Information Security Incident Response Plan; and

- Creation of Ransomware Response Playbooks for your team.

For more information, reach out.